Richard E. Byrd’s Antarctic credentials come from his five expedition to Antarctica from 1928 – 1955 but long before that, in 1912, he had learned to fly as an officer in the U.S. Navy and contributed a number of firsts in that field.

In 1926 with Floyd Bennett as pilot, and Byrd, acting as navigator, he made the first airplane journey over the North Pole, though it is now believed that they fell short by 240 km. Nonetheless, this made him a national hero and he would go on to become the first to fly across the Atlantic from West to East. He was successful, in spite of crash landing in France in bad weather.

In 1928 he turned his attention to the Antarctic and managed to gain the backing of wealthy Americans such as Edsel Ford (he was a good friend of Edsel and his father, Henry Ford), John D. Rockefeller, Jr and the American public. He would go on to name Antarctic geographic features after both Ford and Rockefeller.

Antarctic Expeditions

Byrds first Antarctic expedition (1928-30)

Byrd’s first Antarctic expedition (1928–30), sailed to the continent in October of 1928 and set up a large base on the Ross Ice Shelf, called Little America. This was the first of the American bases on the continent and was well-equipped.

Flights were made from this base and they discovered new mountains and a large area of unknown territory, Marie Byrd Land, which Byrd named after his wife (this area is the unclaimed territory in Antarctica)

On November 29, 1929, Byrd, and his companions would become the first to fly over the South Pole. The flight took 19hrs to fly from Little America to the Pole and return.

Byrds Second Antarctic expedition (1933-35)

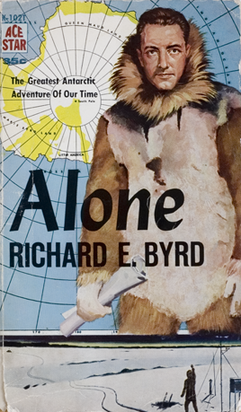

In 1933–35 a second Byrd expedition visited Little America with the aim of mapping and claiming land around the Pole; he extended the exploration of Marie Byrd Land and continued his scientific observations. In 1934 Byrd spent five months alone in a hut, buried beneath the ice, at a weather station named Bolling Advance Base, almost 200 km south of Little America. It almost killed him.

Carbon monoxide (CO) is a colourless and odourless gas which is initially non-irritating. It is produced during incomplete burning of organic matter. This can occur from motor vehicles, heaters, or cooking equipment that run on carbon-based fuels.

Unfortunately, it is fairly common and is a significant hazard in the Antarctic environment because stoves are used in poorly ventilated shelters (e.g. tents, snow caves and igloos). Many polar explorers have died or barely escaped death from carbon monoxide for this reason.

The reason it is so dangerous is because when it is inhaled it combines with the haemoglobin in red blood cells and prevents them from carrying oxygen.

Even in very low concentrations (e.g. 0.06%) it can block half of haemoglobin’s capacity to transport oxygen. The symptoms in mild cases can be dizzyness, headaches and confusion but fatigue, numbness, chest pains, heart palpitations and visual disturbances can also be present. Severe cases may result in a coma.

Unfortunately, carbon monoxide is eliminated from the body very slowly without medical intervention and it continues to cause tissue damage as long as it is present.

So you can continue to suffer symptoms from a few days or weeks to even two years after exposure and can include memory impairment and personality changes. Treatment requires 100% oxygen and a hyperbaric chamber gives the best results.

Admiral Byrd, alone in his hut, was probably the most famous instance of Carbon Monoxide poisoning in Antarctica.

It was the dead of winter, permanent darkness and he was hundreds of kilometres from the nearest support. A poorly ventilated stove resulted in carbon monoxide poisoning from which he narrowly escaped with his life.

His strange radio reports back to base made his officers concerned and they mounted a rescue mission which saved his life. It took him a long time to recover and he writes of his experiences in his book ‘Alone’.

Byrds third Antarctic expedition (1939-41)

Byrd’s third expedition was financed and sponsored by the U.S. government after President Roosevelt asked Byrd to command the U.S. Antarctic programme. This time they again used the Little America base but also set up on Stonington Island, near the Antarctic Peninsula.

This expedition would complete extensive studies of Antarctic geology, biology, meteorology and continue exploring new areas. Due to the impending involvement of America in the Second World War, Byrd was recalled to active duty in 1940 and assigned to the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. The expedition continued without him.

Byrds fourth Antarctic expedition (Operation High Jump) (1946-47)

Operation High Jump involved 4,700 men, 13 ships (including the aircraft carrier Philippine Sea), and 25 aircraft. It was the largest Antarctic expedition ever attempted and would map and photograph almost 1,400,000 square km of the Antarctic continent, especially the coastline. Byrd made his second flight over the South Pole and was involved in a number of other flights. In 1948 the U.S. Navy produced a documentary about the operation. It was called The Secret Land and won an Academy Award for best documentary.

It was this Expedition which figures heavily in conspiracy theories where it is claimed that Byrd’s flotilla encountered Nazi UFO’s and a pitched battle ensued resulting in the defeat of the American forces. None of it is true but that doesn’t stop the story continuing to do the rounds.

Byrds fifth Antarctic expedition (Operation Deep Freeze)

By 1955 Byrd was in charge of the United States’ Antarctic programme and supervised the U.S. Navy’s Operation Deep Freeze, which was sent to support the International Geophysical Year (1957–58). This was Byrd’s final visit to Antarctica and although he was only there for a week, he also took his last flight over the South Pole on January 8, 1956. This expedition also established permanent Antarctic bases at McMurdo Sound (McMurdo Station) and the South Pole (Amundsen-Scott Base).

Byrd’s Accomplishments

Richard E. Byrd invented the aerial sextant and wind-drift instruments in the years after World War I which dramatically improved the science of aerial navigation and were used to a large extent on his own expeditions.

He sits in my section on the Mechanical Age of Antarctic Exploration because of his use of aircraft (ski-planes, helicopters and seaplanes), tractors, bulldozers, radios and modern technical resources to assist him in expanding our knowledge of Antarctica.

Byrd wrote a number of books about his adventures (e.g. Skyward, Little America, Alone, Discovery, To the Pole) which helped cement his fame and his understanding and use of the media made him into a national hero. When he died in 1957 at the age of 68, he was one of the most highly decorated officers in U.S. military history, having received the Congressional Medal of Honour, Navy Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross and the Silver Life Saving Medal, as well as numerous medals and awards from various geographical societies and foreign nations.

A crater on the moon is named after him as were a couple of U.S. Navy ships, some schools, and there are two memorials dedicated to him in New Zealand at Wellington and Dunedin, due to the fact that Byrd was fond of using New Zealand as his departure point for some of his expeditions to Antarctica.

Admiral Richard E. Byrd – a true Antarctic hero.