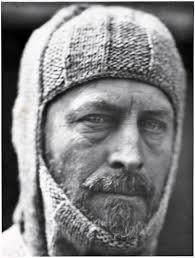

DOUGLAS MAWSON AND THE NIMROD EXPEDITION

An Australian geologist who became Australia’s greatest Antarctic explorer. He participated in Shackleton’s ‘Nimrod’ expedition and then went on to lead three further Antarctic expeditions. His contribution to our knowledge of Antarctica was outstanding.

In the Heroic Age of Antarctic exploration (1897-1922) the names of expeditions were often referred to by the name of the ship that brought the explorers to Antarctica. The Nimrod was Shackleton’s ship that he used for the The British Antarctic Expedition 1907–09

On this expedition,Australian geologists Professor Edgeworth David and Douglas Mawson, as well as 5 of Shackleton’s men made the first ascent of Erebus, the 3,794 metre high active volcano. It was first sighted and named by Captain Ross in 1841. Professor David’s party reached the crater rim on 10 March 1908 after a strenuous five-day climb.

By October 1908 the men had rested and were ready to start their ambitious programme of exploration. Shackleton’s party of four would travel towards the South Geographic Pole (The South Pole), while Edgeworth David’s Northern Sledging Party of three men, (Professor David, Douglas Mawson and the naval surgeon Alistair Mackay) would search for the South Magnetic Pole on what was to be an epic journey.

The following story is taken whole from the ‘Spirit of Mawson’ website which is worth a look here. It tells the story so well I don’t think I could do better.

With Mawson acting as pathfinder the three men trudged northward on the sea ice along the edge of Victoria Land. Making slow progress because of the heavy loads and soft snow, the men were forced to cache some of their supplies and marched on with meagre rations supplemented by seal and penguin meat.

Following the needle on the dipping compass that Mawson was using to guide their way, the men were disappointed to discover that the South Magnetic Pole was further inland than they had initially supposed.

Stoically, they climbed the Drygalski Ice Tongue, carefully negotiating the crevasses, and collecting geological samples as they went. Crossing the crevasses was a delicate operation and all three men skirted with disaster.

At one point Mawson disappeared from view and was found dangling over a deep crevasse suspended by his harness attached to the sledge.

By 15 January 1909 the men were on the Antarctic Plateau – some three thousand metres above sea level – and calculated that they had only fifteen nautical miles (about twenty-eight kilometres) to reach the South Magnetic Pole.

Much like Shackleton, they decided on one final dash to the Pole. Setting out the next day, they left most of their gear with the sledge and pushed on. Hoisting their Union Jack, they claimed the area for the British Empire and after taking a photograph turned, starting back on their long trek home.

With supplies perilously low, the men forced themselves to march back to the coast, hoping that they might be picked up by the Nimrod.

Frost-bitten and exhausted, the men struggled on to their depot and reached it on the morning of 5 February. They were astonished when only a few hours later they heard a rocket; it was the Nimrod.

Only later did the men discover how lucky they had been. The ship had passed by the area several days earlier, heading north but had chosen to return as some of the area had been obscured by fog.

The team had traveled for 122 days, covering a distance of 2030 kilometres, with no dogs or ponies, carrying more than half a tonne of equipment and supplies.

It was the longest unsupported man-hauling journey in history – a record that remained unbroken until the 1980s – and gave the most accurate fix yet on the location of the South Magnetic Pole.

The South Magnetic Pole’s position fluctuates, even on a daily basis, but it is currently located off the coast of Antarctica, in the ocean, some 2860km from the geographic South Pole. It is moving 10–15km to the north-west every year but in 1909 it was accessible over land.

THE TRAGIC FAR EAST SLEDGING JOURNEY

Mawson would go on to organise his own expedition, the Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1910-1914, which landed at Cape Dennison, Commonwealth Bay, in Antarctica on January 8, 1912 .

As part of that exploration Mawson and his two companions, Ninnis and Mertz, left Cape Dennison on November 10, 1912 using dog sleds and 16 dogs to explore the coast to their east.

It was to be a two month trek. They crossed two heavily crevassed glaciers that gave them some fearful moments but within a month they had travelled over 500 km. Crevasses are large cracks in glaciers and are often covered by snow making them difficult to see and a danger for explorers. They can be up to 100 metres or more deep.

After damaging one of the sleds they had to abandon it and loaded one of the other sleds with most of their load. It would be pulled by their strongest dogs. Mertz took the lead on skis looking out for crevasses. Mawson followed with the second lighter sledge and Ninnis took up the rear with the heaviest sledge.

Mertz crossed a crevasse via a snow bridge and called out ‘Crevasse’. Mawson crossed over safely as well, calling back to Ninnis to warn him. Mertz continued on for five minutes and looked back but could see no sign of Ninnis. Mawson stopped as well to see what Mertz was looking at. Ninnis was gone!

Mawson rushed back, soon joined by Mertz, only to look down the crevasse and at a depth of about 45 metres they could see the back of Ninnis’ sledge. The crevasse actually went deeper still and there was no sign of Ninnis.

They did not have ropes long enough and after hours of calling and waiting realised their friend was gone. They read the burial service and a few hours later, dejected, began their homeward trek.

Unfortunately, most of their food was on the lost sledge. They realised they would have to eat the dogs if they were to make it back alive (difficult for Mertz especially since he was a vegetarian).

They did make it about 350 km back towards their hut at Cape Dennison, eating the dogs that pulled them till there were none left. They were becoming weaker and weaker. They were eating the dogs livers as well without knowing that dog livers contain high concentrations of Vitamin A which is toxic in large doses.

Eventually Mertz became too ill to go on and Mawson cared for him in their tent until Mertz died on the morning of January 8th, 1912. Mawson continued on alone. His skin was peeling from his feet, he had frostbite and his body was in a bad way from Vitamin A poisoning.

Then, to make matters worse he fell down a crevasse, saved by the fact he was tied to his sledge by a rope and the sledge didn’t crash down upon him. In spite of his weakened condition he managed to drag himself out and set up his tent.

After resting he continued on and by January 28 he had reached Commonwealth Bay. The next day he found a food cache left by his men earlier that day. A few days later he reached the shelter of ‘Aladdin’s Cave’, a shelter they had built previously. There he found three oranges and a pineapple. Fresh food meant that his ship ‘Aurora’ had arrived recently to resupply them.

He finally staggered down to the Hut at Cape Dennison to be met by five of his men. Unfortunately, the ship had just left and he would have to wait another ten months for its return and his trip home to Australia.

In the meantime he would have a chance for his body to recover from his ordeal. But the deaths of Ninnis and Mertz weighed heavily on all of them.

The two Glaciers that the party crossed are now named Ninnis and Mertz in honour of the two men and a memorial cross in memory of the two men was placed on Azimuth Hill overlooking Cape Dennison.

An epic but tragic tale from Antarctic history.

HOME OF THE BLIZZARD

Mawson had taken many of the photographs on Shackleton’s Nimrod expedition 1907-09, so he recognised the value of photography for documenting scientific exploration and for inspiring the public and the government to donate funds for future trips to Antarctica.

In light of this, Mawson appointed Frank Hurley as the expedition photographer for his Australasian Antarctic Expedition 1911-1914 and Hurley went to great lengths to capture images from the expedition.

Cape Denison proved itself to be incredibly windy, with gusts reaching as much as two hundred kilometres an hour and Hurley built himself a small ice shelter so he could film the men working but, at the same time, protect his camera from the wind and snow.

In 1913 Hurley returned to Australia where he assembled the film. The film was silent without captions and would most likely have been screened accompanied by live narration. It was released in 1913 to popular acclaim to assist with raising funds for Mawson’s return.

Originally titled ‘Life in the Antarctic’ the name was changed to the more dramatic but apt ‘Home of the Blizzard’. The film helped to raise awareness of the polar region, revealing its beauty and the courage of the men who worked there.

When the film was shown in England it was seen by explorer Sir Ernest Shackleton, who later appointed Hurley as official photographer for his 1914 polar expedition.

Sir Douglas died at the age of 76 in 1958 and you can read this article published on the day of his passing.