SCOTT’S ANTARCTIC MOTOR SLEDGES

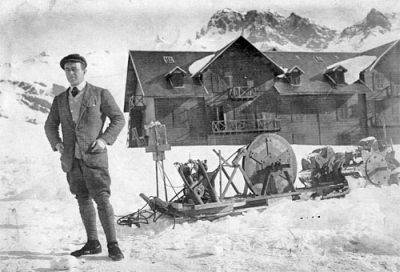

In 1908 French Antarctic explorer Jean-Baptiste Charcot and Robert Falcon Scott, who were both unconvinced by dog-hauling sledges, conducted the first motor sledges test at the Lautaret Pass in the French Alps, near the Hotel des Glaciers (Glacier Hotel).

Two French companies (Dion-Bouton) worked together to produce the sledges that they were willing to offer to both expeditions.

Charcot tried a 200kg motor sledge, which was mildly successful whereas Scott tried a 750kg sledge which sank in the snow, stopping the chain rotation and so the motor. In spite of this, the appeal of the motor sledge was its capacity to carry tonnes of supplies as compared to a pony (182kg) a man (90kg) or a dog (45kg)

In 1909, Charcot shipped his motor sledges to Antarctica on his boat the Pourquoi Pas? considering them as an experiment for future expeditions and relying on man-hauling for the party.

Scott appears to have abandoned the French designs and decided to use a motor sledge designed and patented by Major B. T. Hamilton. He had three built by the Worsley company in Britain for his Terra Nova expedition of 1910-13 and they were field tested in Norway with the help of Engineer Commander R. Skelton.

Unfortunately, the weight of Scott’s sledges was a problem and so was the reliability of the engines in Antarctic conditions. They got off to a bad start when offloading one of the sledges at Cape Evans.. It broke through the ice and sank to the ocean floor.

The remaining two sledges produced mixed results. They did initially assist the party to some degree but Scott wrote:

“Just after starting, picked up a cheerful note…saying all well with motors, both going excellently. [This splendid beginning did not last.] … It appears they had a bad ground on the morning of the 29th [October]. … Some 4 miles out we met a tin pathetically inscribed, ‘Big end Day’s motor No. 2 cylinder broken.’ Half a mile beyond, as I expected, we found the motor, its tracking sledges and all. Notes from Evans and Day told the tale.” In short one of the machines was broken and could not be fixed on the trail. “They had decided to abandon it and push on with the other alone. … So the dream of great help from the machines is at an end!”

Eventually the motor sledges were abandoned and Scott would make the attempt to reach the South Pole using dogs, ponies and finally man-hauling. They reached the Pole but were beaten there by Amundsen, and tragically Scott and his party perished on the return journey.

Following Scott’s tragic death at the South Pole, Jean-Baptiste Charcot decided to have a monument erected in his honour. The monument took the shape of a cairn, similar to those that the polar explorers built using stones to mark out their route and store provisions.

The monument was erected in August 1913 at the Alpine Botanical Garden at the modern-day Route du Galibier in France. Over 200 people travelled from Grenoble and Briançon by sleigh to attend the event.

Following the speeches, Charcot officially handed over the monument to the safekeeping of the University of Grenoble and entrusted it to the local people. the Alpine Botanical Garden transferred to its current site in 1919 and the Cairn was moved there in 1921.

Although the sledges were somewhat of a failure Scott had the strong belief that later designs would prove extremely useful in the Antarctic environment and his vision was eventually proved right with the development of modern snowmobiles and their continued use in Antarctica.