ANTARCTICA’S SUCCESSFUL PLANT EATING DINOSAUR

The discovery of Lystrosaurus fossils at Coalsack Bluff in the Transantarctic Mountains by Edwin H. Colbert and his team in 1969–70 helped support the hypothesis of plate tectonics.

Plate tectonics is a theory explaining how the continents sit on large plates in the Earth’s crust and these plates slowly move over time carrying the continents with them.

Lystrosaurus had already been found in southern Africa as well as in India and China so when it was found in Antarctica it indicated that at some point in the distant past these places were joined (in the prehistoric super-continent of Pangaea).

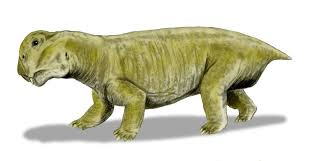

Lystrosaurus was a small, plant-eating dinosaur living around 260 million to 240 million years ago and its first fossil was discovered by a missionary in 1867.

Lystrosaurus was a strange looking beast and had a face only a mother could love. It was the size of a pig weighing around 90kg, with no fur and a very unattractive face.

Found all over Antarctica, parts of Asia and South Africa we know it was very successful and abundant since Lystrosaurus fossils found in some fossil beds make up more than 90% of the deposits. But I have to point out Antarctica was not over the South Pole at the time. It was still slowly moving south so it was a warmer environment than the Antarctica of today.

Lystrosaurus also has the distinction of surviving the Permian-Triassic Extinction Event (known as the “Great Dying”). This was the Earth’s most severe known extinction event, where almost 96% of all marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species became extinct. It was also the only known mass extinction of insects.

Anyway, little piggy Lystrosaurus managed to survive it all and though there are a number of theories no-one is quite sure why. However, a recent paper published in ‘Scientific Reports’ suggests it was because it lived underground, moved around a lot, and grew up very fast, and didn’t get very old.

Before the extinction event Lystrosaurus lived for about 13 years, but after the extinction event, paleontologists found that they lived only two to three years. They also decreased in size to that of dogs. But they were still spreading.

This new paper concludes that that’s because they starting reproducing earlier and more often than normal in the face of extinction, which allowed them to boost their numbers while other animals slowly died out, unable to keep up.