Antarctica: The largest volcanic region on Earth

We know that Antarctica is volcanically active because we can observe the smoke plume from Mount Erebus (the only above-ground volcano active in Antarctica) and scientists have detected under-ice heat sources. Marie Byrd Land (in the unclaimed sector) has 18 volcanoes buried under the ice with some active and melting some of the ice from below (please don’t assume this is the cause of the ice cap melting, it may contribute as in the Pine Island Glacier, but most melting is occurring on the surface and from increasing warm water melting the ice shelves from underneath).

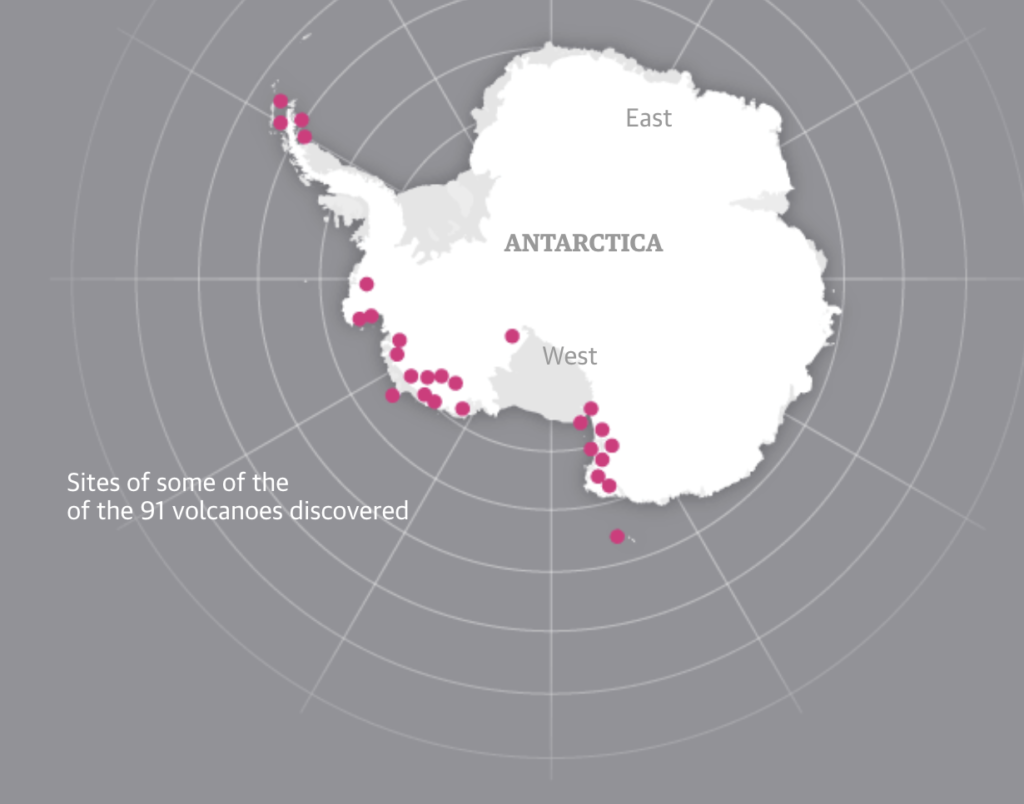

Many still active volcanoes also dot the Antarctic landscape in western Ellsworth Land and the coasts of the Antarctic Peninsula, and in Victoria Land as well, but along the entire coast of East Antarctica only one volcano exists, Gaussberg (or Mt Gauss) which is an extinct volcano.

Although the main volcanic activity is concentrated in the volcanic Scotia Arc, between South America and Antarctica, recently scientists have uncovered what appears to be the largest volcanic region on Earth, even more so than east Africa’s volcanic ridge, currently rated the densest concentration of volcanoes in the world.

The Antarctic volcanic region lies two kilometres below the surface of the Antarctic ice sheet that covers west Antarctica. There, Edinburgh University scientists have found 91 previously unknown volcanoes, the highest reaching a height of almost 4,000 metres (they range in height from 100 to 3,850 metres)

These newly discovered volcanoes are all covered in ice sometimes as much as 4 km thick. The volcanoes are active and concentrated in a region known as the west Antarctic rift system, stretching 3,500km from Antarctica’s Ross ice shelf to the Antarctic peninsula (Here is a list (incomplete) of Antarctica’s volcanoes and their co-ordinates).

The concern is that the pressure of the ice on the volcanoes is keeping their activity subdued but if the ice goes they are likely to become more active as has happened in Iceland and Greenland in the past. Decreasing pressure due to melting ice could result in eruptions which may further destabilise the ice sheets. An eruption may not reach the surface but it would melt the underlying ice turning it to water and allow it to work as a lubricant, making the glacier flow more quickly to the sea. This would lead to sea level rises