The First TransAntarctic Flight

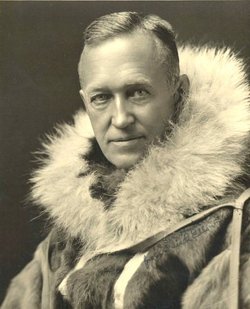

Lincoln Ellsworth was an incredibly wealthy individual due to his father’s business interests and began his career in polar exploration in 1925, when he, Roald Amundsen and a small team set out to be the first to fly to the North Pole in two Dornier flying boats,

After an eight-hour flight, they landed in open water between ice floes but soon realized that they were short of the Pole by some 193 km (120 miles). The open water was soon hemmed in by ice and the two planes became separated. One plane was damaged and they spent 24 days trapped in the ice before managing to fly out in the undamaged plane and return to Spitzbergen.

They would reach the North Pole the following year in the airship Norge and again were almost lost when they were surrounded by thick fog, covered in ice and their radio failed. They managed to find safety at the trading post of Teller, near Nome, Alaska.

Ellsworth next set his sights on Antarctica. With the help of Australian Hubert Wilkins, who would set up bases for him, he intended to fly from Admiral Byrd’s Little America base in the Ross Sea and reach the Weddell Sea on the other side of the continent and return, making him the first to accomplish a transantarctic flight.

He would make three attempts. In the first attempt in 1933-34 they bought an expedition ship which they renamed the Wyatt Earp (Ellsworth was a fan) and a plane they named the Polar Star. The plane had a range of 11,265 km (7000 miles) and could land at the slow speed of 68 km/hr (42 mph)

Despite a heavy ice pack they arrived near Little America and the Polar Star was placed on the snow where Ellsworth and his pilot took the plane on a thirty-minute test flight flying over Roald Amundsen’s old trail that lead to the South Pole. Everything worked well but unfortunately the Polar Star was left overnight on the ice, which began breaking up, and damaged the plane. It had to be returned to the US for repairs and the expedition was called off.

For his second attempt (1934-35) Ellsworth decided to fly from the Weddell Sea to Ross Island on a one-way attempt as it made more sense from a safety point of view if they were forced down. Unfortunately, on starting the plane, an engine rod broke and they had no spare. By the time they had secured a new part the snow fields had thinned making for more difficult take-offs and fog and mild temperatures destroyed any chance of flying.

On the third attempt (1935-36) in November 1935 the Polar Star had been tested and was ready for its flight. Initially they flew around the Antarctic Peninsula and then headed southwest

Ellsworth made an entry in his journal:

‘Heading for unknown. Bold and rugged mountain peaks across our route lay ahead, some of which seemed to rise almost sheer to 12,000 as far as the eye could see. I named this range “Eternity Range”.’

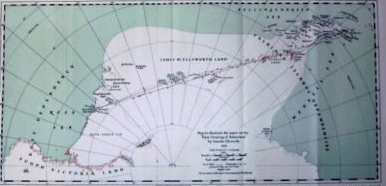

Flying at 3,048 m (10,000 ft), at one point they lost the use of their radio due to a defective switch and did not regain contact. Once they reached 80°W they discovered a vast plain and Ellsworth dropped an American flag. He named the area after his father and it became James W. Ellsworth Land.

After 13 hours in the air they decided to land as visibility was deteriorating and they needed to determine their position. They landed and set up camp at 79° 15′ S, 102° 35′ W. After 19 hours on the ground they took off again for Little America but had to land again 30 minutes later due to worsening weather conditions and were stuck here for three days. Another take-off and 50 minutes in they were forced down again and then a blizzard hit. They were stuck in their tent for three days but they were only 500 miles from their goal. Their plane had been partially buried from the snowstorm and the next few days were spent digging it out.

They took off again and landed after four hours to check their fuel and location. Now they were only 241 km (150 miles) from their goal. Another flight and an hour later they were forced to glide to a landing when their engine died. They knew they were close to Little America but were not sure where it was and made three attempts over a number of days to find it. It was 26 km (16 miles) away and they reached it 11 days after their landing. They settled in to await the arrival of their ship Wyatt Earp.

The governments of Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, concerned about the loss of radio contact, sent the ship, Discovery ll on a rescue mission. The men were to spend two months alone at Little America before being rescued. The ship reached the Bay of Whales and Little America and was followed soon after by the Wyatt Earp. Discovery ll retrieved Ellsworth whose foot had become infected and he was treated on board the ship. Ellsworth’s pilot, Herbert Hollick-Kenyon, went to the Wyatt Earp and stayed behind to retrieve their plane which was refuelled, flown to the Bay of Whales and loaded aboard the Wyatt Earp.

Their trans-antarctic flight covered 3541 km (2200 miles) and they spent a total of approximately 20 hours in the air. More than half the distance covered 1931 km (1200 miles) was over previously unexplored territory and this would be the longest flight in polar history, until it was equalled in 1956.Ellsworth would make one more trip to Antarctica and he died in 1951, aged 71 in New York. Hollick-Kenyon died at age 78 in 1975 in Vancouver, a year after his induction into the Canadian Aviation Hall of Fame (although he was originally born in England).

Ellsworth is relatively unknown today, much like Australia’s greatest adventurer, Sir Hubert WIlkins. Such a pity for such a great polar explorer.