Everyone seems to like penguins and they are perhaps the most popular animal in Antarctica. With their funny antics and sometimes human-like behaviour what’s not to love?

There are 18 penguin species in the world but only 8 of them are found in Antarctica and only 4 of these spend their lives on the continent (if you include the sea ice as part of the continent). The other four only live there part of the year.

The penguins that live in Antarctica year round are the Adelie, Chinstrap, Emperor and Gentoo penguins. Adelie and Emperor penguins breed on the shores of Antarctica and its nearby islands. Chinstraps breed on some of the islands around Antarctica and Gentoos are found on both Antarctic and sub-Antarctic islands. Another four species (the King, Royal, Southern Rockhopper and Macaroni penguins) live only on the subantarctic islands.

Penguins are a type of flightless bird that is highly adapted to the ocean environment and although somewhat clumsy on land they are excellent swimmers, and can dive to great depths (the Emperors go as deep as 500 metres). Their streamlined shape allows them to glide easily underwater and they are extremely agile. Due to the frigid conditions in Antarctica they have developed a thick layer of fat (blubber) and over-lapping, short feathers that provide insulation against the cold.

They also have an amazing system of ligament linkages that allow them to move their feet and flippers without requiring muscles or bloodflow in those appendages which prevents them from freezing.

Penguins generally feed on small fish and krill (a small shrimp) but they are also food for other animals, especially leopard seals and killer whales (Orcas) in the ocean and skuas and sheathbills (carnivorous birds) on land. The birds take penguin eggs and attack penguin chicks.

Penguins are only found in the Southern Hemisphere but they extend as far as the equator.

How to identify Antarctic penguins

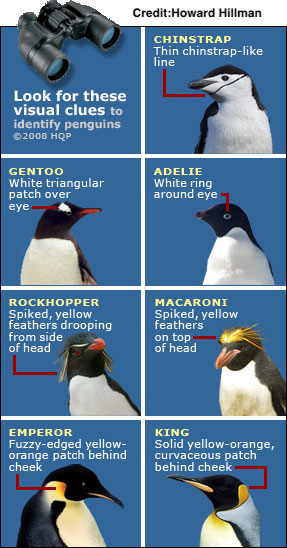

So how do you identify which penguin is which? Well, here is a handy guide. The true Antarctic species are:

Adèlie – The most numerous penguin species. They build their nests out of pebbles and lay two eggs (though only one survives). The Adèlie all have a white ring around their eyes.

Chinstrap – Distributed across Sub Antarctic and Antarctic islands, and the Antarctic Peninsula. They have an obvious thin black line where their chins should be, stretching from ear to ear.

Emperor – They are the heaviest and tallest of all the penguins and spend their entire lives in Antarctica. Emperors are identified by the fuzzy-edged yellowy-orange-gold markings on the side of their head behind their cheeks and on their necks and beaks.

Gentoo – They are the third largest penguin species and only breed in areas that are clear of snow and ice. Identified by the white patch above and behind the eye

The three sub-Antarctic species are:

King – They live on sub-Antarctic islands and don’t make a nest. Instead, they carry the egg on their feet covered by a brood pouch (like Emperors). They are the second largest penguin after the Emperor and have a solid yellow-orange-gold curved patch at the rear of their cheeks and a similar colouring on the necks and beaks.

Macaroni – They live on the open ocean, only coming ashore to breed, where they lay two eggs. They have spikey yellow /orange feathers on top of their head and a thick, dull orange beak with a small section of pink to the rear. Their legs and feet are pink.

Rockhopper- They prefer to live on green pastures and rocky areas and their range extends from the southern regions of Chile to the sub-Antarctic islands. They have spikey yellow feathers drooping down the side of their heads.

Royal – They only exist on three sub-Antarctic islands (Macquarie Island, and the much smaller Bishop and Clark Islets). They look similar to Macaroni penguins. However, royals are up to 20% larger than macaronis and also tend to have white to pale grey faces compared to the black-faced Macaronis. They also have yellow plumes on their heads.

Hopefully, if you get down to Antarctica you’ll be able to identify them now and you can also use the guide photos below. Good luck.

What penguins have to deal with in Antarctica

It is not an easy life being a penguin in Antarctica. Besides the extreme cold penguins have to deal with overfishing of their food supply, fishing net entanglements, skuas eating their eggs and attacking their chicks, leopard seals bashing them on the water till their skin flails off before eating them, chemical wastes and pesticides have now been found in their tissues in Antarctica and maybe even stress from all the tourists that keep pestering them (though we’re not sure)

Cherry-Garrard, a member of Scott’s party, and the first to collect Emperor penguin eggs in winter, said ‘Take it all in all. I do not believe anyone on Earth has a worse time than an Emperor Penguin’

The Emperor penguins stay throughout the long cold winter protecting their eggs huddled in a group that slowly rotates and those on the outside are replaced regularly by others so that none bear the full brunt of the cold and wind.

Early explorers commented on mass die-offs of penguins caught in unusually bitter weather, the chicks being especially susceptible, but their problems are increasing.

Due to climate change (Yes, it’s real) temperatures in the Antarctic have risen five times faster than the average rate of global warming. What this does is create higher precipitation in both rain and snow.

Antarctica is very dry and rain was rarely recorded there until about 25 years ago. The penguin chicks can cope with snow but the rain saturates their downy feathers and they can’t keep warm, then if the temperatures drop, they freeze to death.

Severe snowstorms have also increased and since penguins won’t leave their nests because they are protecting their chicks and eggs, the snowfall is sometimes so deep that penguins become buried on their nests.

There have been many instances of colonies of mummified penguinsbeing found. They had been buried alive in sudden blizzards. We know it has also happened in the past.

Hundreds of mummified penguins were found littering the ground on Long Peninsula in east Antarctica. There seem to have been two bouts of extreme weather over the past 1000 years which caused the die off

The only difference from the past is that now the events are happening more frequently. It’s tough being a penguin in Antarctica.

Why would you eat a penguin?

Well, nowadays you probably wouldn’t and besides they are protected in Antarctica. However, in the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration (1897-1922), despite the many tonnes of stores that early explorers took with them, they often had to wait through the winter before they could start exploring in the summer.

To conserve their stores they would eat penguin and seal meat and also feed it to the dogs that pulled their sleds. Penguins and seals also contain blubber (fat) which could be used as a fuel for cooking and to melt ice for drinking water.

But perhaps more importantly, scurvy (a disease caused by lack of vitamin C), could be prevented by eating fresh penguin (or seal) meat, especially if it was not overcooked. Humans only store enough Vitamin C for about 3 months so deficiencies could occur on long sea voyages or overwintering in Antarctica

There were a number of theories about the cause of scurvy – darkness, moisture, lack of exercise, laziness, a lack of oxygen in the tissues, spoiled food or constipation to name a few. Back then they didn’t know about vitamins and vitamin C’s connection with scurvy was not discovered until 1932.

Unfortunately for the penguins it was generally known that fresh meat prevented scurvy and the penguins were very curious so it was easy to kill them.

Today they are protected under the Antarctic Treaty and you are not allowed to go closer than 5 metres to them but it is OK if they come to you, which they often do. Just don’t eat them.

The craziest Easter egg hunt ever!!

Ok, so it wasn’t Easter but it was an egg hunt.

Apsley Cherry-Gerrard was to say ‘And so we started just after midwinter on the weirdest bird’s-nesting expedition that has ever been or ever will be’

Aspley Cherry Garrard, Bill Wilson and Birdie Bowers were with the legendary Robert Falcon Scott on the Terra Nova expedition. This was the expedition where Scott made it to the South Pole, only to find that the Norwegian, Amundsen’ had beaten him to it. Scott and his four companions were to die on their return journey trapped in a blizzard.

But earlier in the expedition in July, 1911, Apsley Cherry-Garrard, ‘Bill’ Wilson, and Henry ‘Birdie’ Bowers set off to collect Emperor Penguin eggs during the Antarctic Winter since there were no known examples of Emperor Penguin embryos.

They travelled almost 100 km to an Emperor Penguin colony through the Antarctic night dragging sledges loaded with supplies. Each sledge weighed 115kg and the temperature fluctuated between -40 and -60 C.

It was so cold that Cherry-Garrard’s teeth shattered from chattering, ‘All my teeth, the nerves of which had been killed, split to pieces’. On reaching their destination they built an igloo and set up their tent to stow their supplies.

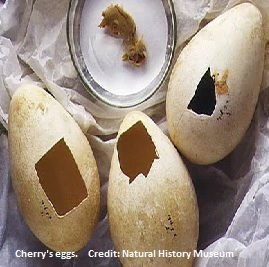

They were trapped in a blizzard and their tent was blown away but luckily they found it the next day when the wind died down. They reached the Emperor colony and retrieved five eggs but only three eggs survived the trip back to their camp.

Though exhausted, they decided to return immediately to their base at Cape Evans. Through terrible storms, dangerous crevasses and frostbite they made it back. All up it took 35 days.

Unfortunately, Wilson and Bowers, would later accompany Scott to the South Pole and die on the return journey. Cherry-Garrard never really got over the loss of his two friends. He did write a book about their adventure though – ‘The Worst Journey in the World’

And what happened to the three penguin eggs?

Cherry-Garrard gave them to the Natural History Museum in South Kensington where the Senior Custodian treated him very rudely. Bureaucracies and officialdom rarely change.

Perhaps not much came of it from a scientific viewpoint but it was a grand adventure and not to be dismissed lightly. Cherry-Garrard battled depression and died in 1959 but he did develop a lifelong affection for the Emperor Penguins.

He once said ‘All in all. I do not believe that anyone on Earth has a worse time than an Emperor Penguin’, for Apsley Cherry-Garrard had lived through similar conditions and survived to write about it.